A field in Oxford, Great Britain, 2015.

When I was 4, my mother used to take me and my sister for long afternoon walks along country roads. My family rented a farm workers cottage on a dairy farm because it was cheap and close to my father's work in Hamilton. Memory has turned those afternoon walks into an idyllic scene of childhood. The privet hedgerows filling the air with their saccharine scent, the wide green fields stretching into infinity and a sky so big I was sure it would fall on us. The plants that grew on the roadside, by the ditches, were a tangle of long weeds and grass: canes of prickly blackberries ripe with fruit, long stalks of sticky paspalum and white yarrow flowers. A number of fields had stands of tall trees, some were oaks and some were weeping willows with bobbed haircuts. In the hot afternoon sun the cattle would shelter under the trees. When people say the word meadow, this is the image that comes to my mind.

In Europe and North America meadow and prairie style gardens have become very popular. They have a garden of Eden sort of look, a landscape untouched by human hands. From an environmental viewpoint meadows are rich with biodiversity, which allows some people to feel they're being environmentally worthy and not just growing another kind of flower garden. Piet Oudolf and Noel Kingsbury are leaders in this area. I'm reading a book they wrote together called Planting: A New Perspective, published in 2013. It's an informative, interesting book, if a little earnest and dare I say it ... elitist. I'm reading Margery Fish's second book 'An All The Year Garden' simultaneously as an antidote, it was published in 1958. The prose is chatty, and utterly charming. Interestingly Noel Kingsbury (who is writing the book on his and Piet's behalf) mentions Margery Fish and the people who make cottage gardens. He says they 'model themselves on 'humble cottagers' creating 'an apparently artless combination of plants which have proved highly popular. The spontaneity is, however, apparent rather than real.' I guess he's trying to say that cottage gardens are contrived, but no more so than meadows, unless those meadows are wild.

Botanic Garden, Oxford, June 2015.

There are, according to The Wiki, 3 different kinds of Meadows. All of them are populated by grasses and wildflowers, and have an absence of woody plants. There are agricultural meadows (fields left to grow and remain uncut), transitional meadows (areas that were once forests and will become forests again if allowed) and perpetual meadows (areas where only grasses and wildflowers will grow such as coastal and alpine areas). Meadows grow in open sunny places and support a diversity of wildlife, especially bees and other pollinating insects, attracted by the many flowers.

Rangipo Desert. A naturally occurring meadow, which because of its alpine climate, high altitude and situation between 3 active volcanoes it hasn't the diversity of plants as other meadows.

Meadows look different to other planting styles. They are gardens on a big scale, with blocks of swaying verticals that seem to blur with the horizon. The experience of looking at a meadow is like looking into one of Monet's huge waterlily paintings. A dreamy soft-focus haze with swirls and patches of colour. Meadows are faded big screen movies, cottage gardens are technicolor on television. Meadows are mesmerizing. They have the same meditative effect on people as gazing at a seascape. I've often wondered if meadows have to be huge to be classed as a meadow. Is a small meadow still a meadow or is it an herbaceous border?

Recently, we had a landscaper around to give us a quote on some paving work. He was young and enthusiastic. We were heartened to see he had graduated with honors from university, and told ourselves we were lucky to have him working on our project. He certainly knew a lot about landscaping judging by the way he talked so confidently about drainage and fencing. Nonetheless, I was surprised how disinterested he was in the plants that adjoined the area to be paved. Maybe he didn't know a lot about plants, maybe my sort of planting scheme wasn't his sort of planting scheme. He did, however, make a positive comment about the brush fencing I'd nailed along the fence, which, as I said in my last blog, was very ugly. I'd assumed, wrongly, that anyone who trained to be a landscaper was not only knowledgeable about plants, but also interested in them. Maybe plants to him were no different then paving slabs or fence pails - landscaping commodities. As he was about to leave, the landscaper looked over at our sycamore tree and asked if we'd ever considered having it removed. It was at this point I realized we saw the world from completely different points of view.

There are two big trees in our back garden: an oak and a sycamore, standing side by side. At a guess I'd put them at 86 years of age. They were probably planted in the mid 1920's when our house was built. Most native trees are evergreen, it's only the exotics that lose their leaves in winter. At the moment the oak and sycamore are tall and bare. Their trunks and branches are covered in a grey lichen, which only adds to their charm. What I notice most about the two trees is their contrasting shapes. The Sycamore grows in the shape of a wineglass, while the oak is your classic friendly tree-shape, a graceful blob on a stalk.

Sycamore tree, Wellington 2011.

Sycamores, while beautiful trees, are out of favour; they drop helicopter leaves in autumn, which sprout like weeds in every crack and hard to get to place. Oaks, while not social pariahs, are far from being fashionable, you'd have to be a lancewood Pseudopanax crassifolius or the New Zealand oak, 'Titoki' Alectryon excelsus to be invited anywhere, but these old school oaks are still respected. Gracious old towns like Cambridge still have large stands of them.

As you can see, my back garden is a mess.

The back garden, autumn, 2016.

It's a long skinny space with 3 ugly fences, a makeshift vegetable garden, a rotary clothesline and two big trees. I started to fantasise about the back garden getting turned into a meadowesque sort of scene. But then I changed my mind for a number of reasons. Our dog has unlimited access to this area and she likes to dig - how long would a meadow garden last before it was dug up? Also, there's a problem with light. The light changes dramatically from winter, when the area is bathed in sun, to summer, when three quarters of it lives in shade thanks to the oak and sycamore trees. I could have a meadow in the small sunny spots, but what do I do with the rest of the space?

And then I remembered a book I had that I'd barely glanced at. I'd bought it at The Salvation Army Family Store for $2.00; it's called 'Wild Gardens: What To Grow, How To Grow It' by Jenny Hendy. While it was written for the northern hemisphere, most of the information looked like it could be applied to a New Zealand garden.

Until I read Jenny Hendy's book I always thought that meadows and prairies were different names for the same sort of thing, not so according to Jenny. A meadow is a field of wildflowers, usually annuals and biennials, and grasses; a prairie is a mixture of tall perennials and clumps of grasses. Meadows prefer poor well-drained soil and prairies like a richer soil. Given I have clay soil, I'm thinking the prairie garden will work best. I re-read Jenny Hendy's instructions on making meadows and prairies and now I feel exhausted. There's a lot of preparation. I always thought that meadow/prairie gardens were easy to make. I assumed that you dug plants and seeds straight into the soil, between the existing clumps of grass. I was so wrong. I'm going to have to dig up the grass, get rid of all the weeds, add compost and then plant it with plants and seeds. Making a meadow or prairie is just as labour intensive and fiddly as making a flower garden.

Talking about flowers reminds me of yarrow. The flower from the roadside meadows of my childhood. I guess that's what I'm trying to recreate in my back garden. Maybe that's what all of us ordinary gardeners are trying to do, get back to our childhood. Wild yarrow is considered a weed in New Zealand because it's so invasive, still it has some helpful properties and nice scented flowers. It's a wound herb and can be used in first aid. Chew it up and place the mush on a wound to stop the bleeding. Something to remember if you skin a knee while on a roadside walk. Apparently, the coloured cultivars are less invasive. I'll look out for some of those for my meadow/prairie garden. I'll sneak in some wild yarrow too, for old times sake. It can have a competition with the sycamore tree; who can take over the garden first?

Yarrow, Achillea millefolium. A photograph by Deni Bown in her book 'Herbal'.

Yarrow isn't an umbellifer but it has the appearance of one, with its clusters of small flowers. If there's one kind of flower that says 'meadow' it's an umbellifer.

Bronze fennel, Foeniculum vulgare

Umbelliferous flowers are, according to Deni Bown in her book Herbal, 'an umbrella-shaped, flat-topped or rounded flower cluster in which individual flower stalks arise from a common centre. Characteristic of the parsley family, once known as Umbelliferae (now Apiaceae).' Here's a list of plants with umbels: fennel, parsley, carrots, angelica, anise, coriander, dill, parsnips, caraway, cow parsley, chervil and lovage. Lots of these guys are going to find a home in my meadow or should I say prairie.

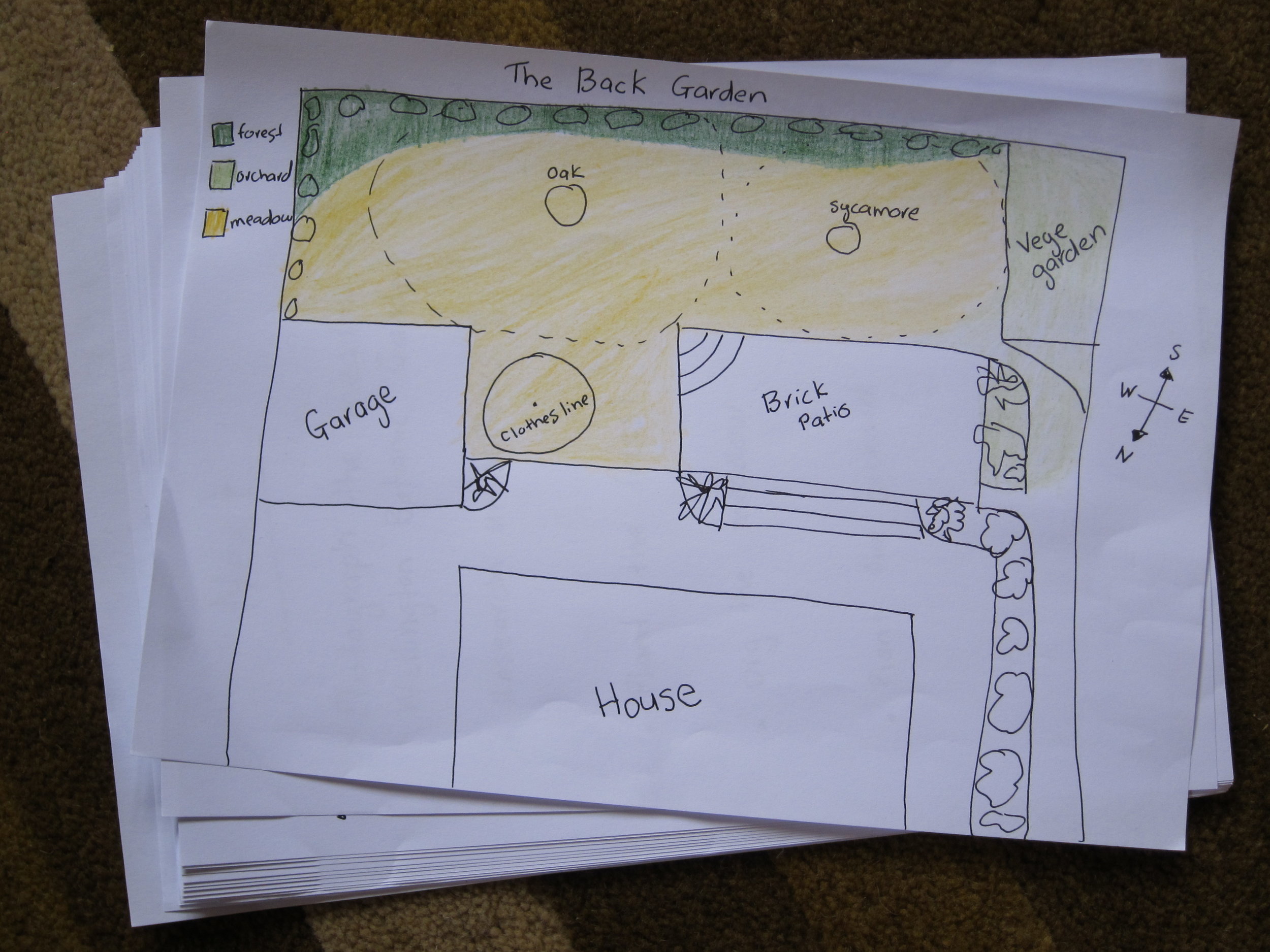

Here's a simple plan of my still-to-be-made garden, which I recently drew up. I'm going to give the illusion of a forest behind the oak and sycamore trees (I have no idea how). This will, I hope, hide the ugly wooden fence and provide privacy. The vegetable garden (that gets no summer sun ) will get turned into a kind of orchard, with fruit trees, bushes and vines, underplanted with meadow plants. The remaining space will get a meadow/prairie treatment where there's enough light and where it's darker I'll grow woodland plants. If it all gets too difficult and I can't keep the weeds out, then I'll cover the entire area in wild yarrow.

A plan for the back garden.